3 ways of shooting yourself in the foot when writing applications in Go

I’ve been using Go for a few years now and today I want to share some experience. This post is about a few funny and somewhat not obvious bad Go patterns. This is 3 ways of shooting yourself in the foot when writing applications in Go.

Channels overflow

Among many other things, Go is great for its concurrent programming model. Goroutines, channels and packages from the standard library like sync offer a great experience when it comes to solving problems with concurrency. Concurrency is also kind of the gateway for new Go users. Some leave because of the lack of certain features that they love from another langage, some stay for the simplicity, or boringness (yes this is a feature), the opinionated toolchain, the welcoming community, or else. Either way, the ability of Go to offer simple yet powerful concurrency primitives has been a critical part of the success of the langage.

But great powers comes with great responsibility, and it’s easy to get carried away with all the new possibilities.

Let’s look at the below code sample, it has a function Run that starts a webserver which reads and JSON decodes a list of image URLs, and sends them into a channel urlChan.

From there, some work is executed in the background, using 3 goroutines:

downloadImagesdownloads images data and stores it in memory.resizeImagesresizes the downloaded images.readResizedImagesreads the resized images, then drops the bytes.

The 3 background goroutines exchange messages by the mean of the urlChan, imageChan and resizedDataChan channels.

The complete code is available here on Github.

func Run(config config.Config) {

urlChan := make(chan string)

imageChan := make(chan []byte)

resizedDataChan := make(chan []byte)

go downloadImages(urlChan, imageChan)

go resizeImages(imageChan, resizedDataChan)

go readResizedImages(resizedDataChan)

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var imagesUrl []string

json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&imagesUrl)

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

urlChan <- imageUrl

}

})

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

func downloadImages(urls chan string, out chan []byte) {

for {

go func(url string) {

resp, _ := http.Get(url)

defer resp.Body.Close()

b, _ := ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

out <- b

}(<-urls)

}

}

func resizeImages(in chan []byte, out chan []byte) {

for {

go func(data []byte) {

img, _, _ := image.Decode(bytes.NewBuffer(data))

newImage := resize.Resize(50, 0, img, resize.Lanczos3)

b := new(bytes.Buffer)

out <- b.Bytes()

}(<-in)

}

}

func readResizedImages(imgs chan []byte) {

for {

go func(img []byte) {

log.Print("read resized image data")

}(<-imgs)

}

}

So this works fine, but there is something interesting here, something that might not be obvious on the first look.

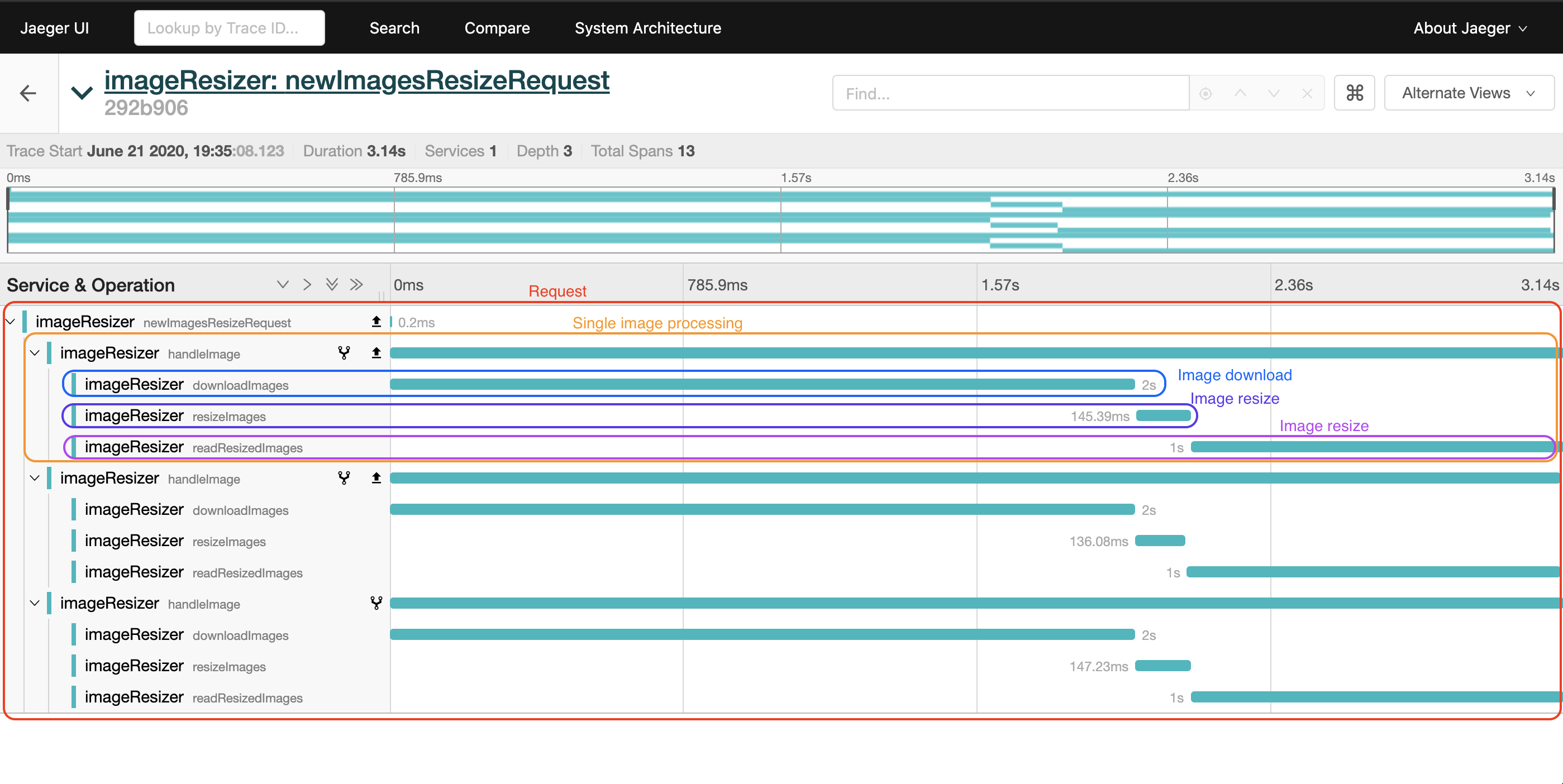

We can run a more instrumented version of the same code and inspect what happens for each request.

We first run Jaeger using Docker.

Jaeger is a tool that helps you instrument applications with traces. Traces are a visual representation of the repartition of the requests time. They can help you to better understand your requests and find bottlenecks.

docker run \

-d \

--network=host \

--name=jaeger \

jaegertracing/all-in-one:latest

Then we run the sample code.

docker run \

-d \

--restart=always \

--network=host \

--memory=200m \

--name=channels \

aubm/random-go-tips channels sequence

Then we send a request using curl.

curl "http://localhost:8080/" -XPOST -d '[

"https://picsum.photos/id/0/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/1/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/2/2560/1440"

]'

On the Jaeger web UI which should be accessible on http://localhost:16686, we filter by service imageResizer, then click at on a generated trace. Here is what we can observe.

From the trace, we can see that despite the fact that the work is distributed across multiple goroutines and channels, processing an image is really a sequential task. At best, we can concurrently process several images. The current code turns out to be over complicated for that.

The below code sample is a simpler version that does exactly the same thing.

func Run(config config.Config) {

urlChan := make(chan string)

go processImages(urlChan)

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var imagesUrl []string

json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&imagesUrl)

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

urlChan <- imageUrl

}

})

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

func processImages(urls chan string) {

for {

go func(url string) {

resp, _ := http.Get(url)

defer resp.Body.Close()

data, _ := ioutil.ReadAll(resp.Body)

img, _, _ := image.Decode(bytes.NewBuffer(data))

newImage := resize.Resize(50, 0, img, resize.Lanczos3)

b := new(bytes.Buffer)

log.Print("read resized image data")

}(<-urls)

}

}

It can be tempting to experiment with these features, but we should make sure that we actually need them. Otherwise we can end up with bits of unnecessarily complicated code.

Now let’s clean up the running containers and move on.

docker rm -f jaeger channels

Unbounded concurrency

Next is a case that I’ve often seen in Go codebases because it can be easily forgotten.

Let’s look at the below code sample.

The function has the standard HTTP handler signature.

From r.Body, which contains the HTTP request body, we read and JSON decode a list of image URLs. If everything went good, then we iterate over these URLs, and for each one, we invoke img.ResizeFromUrl which downloads the image, resize it to the specified width and height and then just drops the bytes.

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var imagesUrl []string

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&imagesUrl); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

if _, err := img.ResizeFromUrl(imageUrl, 100, 0); err != nil {

log.Printf("failed to resize image, url: %v, err: %v", imageUrl, err)

}

}

}

The code is executed sequentially. Because we might be spending a significant amount of time just waiting for the image download to complete, it seems like a reasonnable idea to apply some goroutine magic on top of that.

In this new version, img.ResizeFromUrl is called from a goroutine, and there is one goroutine per URL. A sync.WaitGroup is used to ensure that we do not respond before everything is done.

The service should now be significantly faster.

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var imagesUrl []string

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&imagesUrl); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

wg := sync.WaitGroup{}

wg.Add(len(imagesUrl))

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

go func(imageUrl string) {

defer wg.Done()

if _, err := img.ResizeFromUrl(imageUrl, 100, 0); err != nil {

log.Printf("failed to resize image, url: %v, err: %v", imageUrl, err)

}

}(imageUrl)

}

wg.Wait()

}

Let’s run the code samples with Docker and test it.

Use this command to run the first code sample on port 8080.

docker run \

-d \

--restart=always \

-p 8080:8080 \

--memory=200m \

--name=sequence \

aubm/random-go-tips concurrency sequence

And use this command to run the second code sample on port 8081.

docker run \

-d \

--restart=always \

-p 8081:8080 \

--memory=200m \

--name=unbounded \

aubm/random-go-tips concurrency unbounded

Now we run some tests using curl and measure the elapsed time.

time curl "http://localhost:8080/" --fail -XPOST -d '[

"https://picsum.photos/id/0/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/1/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/2/2560/1440"

]'

(Output)

curl "http://localhost:8080/" -XPOST -d 0,00s user 0,00s system 0% cpu 3,127 total

time curl "http://localhost:8081/" --fail -XPOST -d '[

"https://picsum.photos/id/0/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/1/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/2/2560/1440"

]'

(Output)

curl "http://localhost:8081/" -XPOST -d 0,00s user 0,00s system 0% cpu 1,391 total

The first took 3.127 seconds, the second took 1.391 seconds which is about 2.25 times faster. We can repeat this several times, we should get something close to that ratio. Ok so where is the catch?

The number of URLs that we can send is unlimited, so let’s try and send more.

time curl "http://localhost:8080/" --fail -XPOST -d '[

"https://picsum.photos/id/0/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/1/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/2/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/3/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/4/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/5/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/6/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/7/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/8/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/9/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/11/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/12/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/13/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/14/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/15/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/16/2560/1440"

]'

(Output)

curl "http://localhost:8080/" --fail -XPOST -d 0,00s user 0,00s system 0% cpu 15,846 total

time curl "http://localhost:8081/" --fail -XPOST -d '[

"https://picsum.photos/id/0/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/1/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/2/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/3/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/4/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/5/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/6/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/7/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/8/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/9/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/11/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/12/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/13/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/14/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/15/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/16/2560/1440"

]'

(Output)

curl: (52) Empty reply from server

curl "http://localhost:8081/" --fail -XPOST -d 0,00s user 0,00s system 0% cpu 6,432 total

The first took 15.846 seconds which is close enough to what we should have expected (about 5 times the time that it took to process 3 images).

The second command failed however. Let’s inspect the container to see its state.

docker inspect unbounded | jq '.[].State'

(Output)

{

"Status": "running",

"Running": true,

"Paused": false,

"Restarting": false,

"OOMKilled": true,

"Dead": false,

"Pid": 3774,

"ExitCode": 0,

"Error": "",

"StartedAt": "2020-06-21T15:42:45.4609026Z",

"FinishedAt": "2020-06-21T15:42:45.1495252Z"

}

We can see from there that the container has been OOMkilled. The request made the container load too many images in memory. We did not anticipate that when the second version of the code was implemented. Now a single request could bring the server down for all users. One good practice when it comes to writing production endpoints is to have homogeneous request profiles, in term of resources consumption. That is, not having one request consuming 1MB of memory, and another consuming hundries of MB of memory. This makes it easier for scaling the application without wasting too much resources.

For our memory issue here, we would need two things:

- Find a way to limit the amount of downloaded data on a per image basis.

- Limit the number of images processed simultaneously.

We’ll focus on the latter, which we can implement using a worker pool.

The below code sample starts a fixed number nbWorkers of goroutines that concurrently consume image URLs from a shared channel jobs.

Once the goroutines are started, all image URLs are added to the channel, then the request waits for all the images to be processed.

This is slightly more complicated but now there is a maximum of 3 simultaneous invocations of img.ResizeFromUrl, which should help us control the consumed memory per request.

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var imagesUrl []string

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&imagesUrl); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

nbJobs := len(imagesUrl)

nbWorkers := 3

jobs := make(chan string, nbJobs)

wg := sync.WaitGroup{}

wg.Add(nbJobs)

for w := 1; w <= nbWorkers; w++ {

go resizeImagesWorker(jobs, &wg)

}

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

jobs <- imageUrl

}

close(jobs)

wg.Wait()

}

func resizeImagesWorker(imagesUrl chan string, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

for imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

if _, err := img.ResizeFromUrl(imageUrl, 100, 0); err != nil {

log.Printf("failed to resize image, url: %v, err: %v", imageUrl, err)

}

wg.Done()

}

}

Now let’s run it with Docker.

docker run \

-d \

--restart=always \

-p 8082:8080 \

--memory=200m \

--name=pool \

aubm/random-go-tips concurrency pool

Then test it with the same request that previously crashed.

time curl "http://localhost:8082/" --fail -XPOST -d '[

"https://picsum.photos/id/0/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/1/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/2/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/3/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/4/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/5/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/6/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/7/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/8/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/9/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/11/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/12/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/13/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/14/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/15/2560/1440",

"https://picsum.photos/id/16/2560/1440"

]'

(Output)

curl "http://localhost:8082/" --fail -XPOST -d 0,00s user 0,01s system 0% cpu 5,497 total

This is way better, the request worked and went way faster than the original sequential version.

Now let’s clean everything up and move on.

docker rm -f sequence unbounded pool

Unhandled context cancelation

The third way to shoot yourself in the foot has to do with context. And more specifically, what happens when we forget to handle context cancelation.

Context is a package from the standard library whose primary focus is to help with cancelation of long running or heavy computation goroutines.

So you have a variable of type context.Context, the convention for the name of that variable is ctx. Calling ctx.Done() gets you a channel which produces a value when the context is canceled.

The package provides functions for creating contexts that will automatically be canceled at a given time, after a given duration, or when manually using a provided callback function.

So let’s go back to one of our previous examples. In this one, images are resized sequentially, one by one.

func Run(config config.Config) {

http.HandleFunc("/", handler)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

var imagesUrl []string

if err := json.NewDecoder(r.Body).Decode(&imagesUrl); err != nil {

http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

if _, err := img.ResizeFromUrl(imageUrl, 100, 0); err != nil {

log.Printf("failed to resize image, url: %v, err: %v", imageUrl, err)

}

}

}

So there is no concurrency involved, except that there actually is… in the standard library HTTP server implementation.

There are good chances that a simple web server was one of the first go programs that you ever wrote, probably as part of your discovering journey in the language. And because this is one those things that just work, you might not have reasonned much about how it works internally. Well to be honest, neither did I. But there is one thing that worth keeping in mind: each user request is handled a separate goroutine.

So we know that, and we also know that a goroutine only ends when the function returns. For the above code, this means that if I was to send a request for 1000 images, and cancel that request right away, the server would still be iterating on those 1000 images, even though I’m no longer interested in the response. This is a total waste of resources and we need a way to solve this.

One way to solve this, is by checking ctx.Done() for each iteration on imagesUrl.

Using a select statement, I can early exit the function if the context is canceled, or default to the normal behavior if the user is still there.

func Run(config config.Config) {

http.HandleFunc("/", handler)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil)

}

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

ctx := r.Context()

for _, imageUrl := range imagesUrl {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

log.Print(ctx.Err())

return

default:

if _, err := img.ResizeFromUrl(imageUrl, 100, 0); err == nil {

log.Printf("resized image, url: %v", imageUrl)

} else {

log.Printf("failed to resize image, url: %v, err: %v", imageUrl, err)

}

}

}

}

As you can see, we are reading from r.Context(). In this case, the context is provided to us by the standard http server implementation, which takes care of canceling the context when the client cancels the request.

And there it is, 3 ways of shooting yourself in the foot when writing applications in go!