How my programming skills helped me to become better with my personal finances (part 1)

About two years ago I moved from France to Canada which raised some questions regarding how I would manage money. Some of them had to do with how taxes work. I also wondered what portion of my euros I should convert and transfer to my Canadian bank account. But the question I was most eager to solve was how much money it was going to cost me to maintain a train of life similar to the one I had in France. I had access to other immigrants’ experiences, and I was able to find general trends on the internet to compare the cost of living between different cities around the world. I could also make my own quick observations and realize that I was going to spend significantly more on some expenses such as rent or phone bills, but on the other hand electricity and gas were cheaper.

But all that was not going to be a big help of course since it really depends on your lifestyle. In France, I used to own a car for which I had to spend a big part of my income. Here in Canada where I have a more urban lifestyle, I spend twice as much for my rent, but I don’t need a car. Electricity is cheap, but surely I tend to consume more because winters are colder (or maybe not, because my apartment is better isolated). I could go on and talk about grocery, transportation, insurance, etc. anyway, you get my point: it depends. I bet my expenses don’t have much in common with my next door neighbor’s who for all I know rents a parking lot in the building to park his huge SUV, and goes out in bars and restaurants three times more than I do, but who doesn’t care for the 65 inches TV that sits in my living room and doesn’t flight back in France once every two years to visit his family and friends.

So in the end, do I spend more or less money now than I used to spend in France? I don’t know. If I had to guess, I would probably say yes, but I would not be able to confirm it, and even less to say by how much. I’m not because it’s only two years ago, when for the first time, this very question crossed my mind, which sometimes tends to become euphemistically obsessive about certain topics, that I created a new file on Google Sheets and started keeping track of all my expenses. To me, this was the beginning of a newly discovered interest in personal finance management that has continued to grow each day ever since. I learned a great deal on this personal journey, and progressively put an end to a lot of bad habits I had with money that were part of a general trend towards overconsumption. Some of these bad habits not only could have eventually led me to a certain financial precariousness (even though I’m lucky to have an income above the average), but could also have had severe repercussions on my health in the long run, as on the environment. Before that, I gladly spent my money away on small transactions, not having a clue on how much I spent on things like food or restaurants, only caring to check my online banking on the occasional spark of responsibility, most of the time to do a quick napkin math to check whether I could afford that upcoming less small transaction. As I said, as a programmer working in a big company, I was lucky to benefit from an income higher than the minimum wage. Also luckily I had some common sense and education from my parents, which would at least prevent me from shooting myself in the foot by taking out big loans for things I could easily live without. Still, I was not getting any closer to living in my own house or apartment, or any other project that requires some savings. And I was lucky enough to live in a country where everybody expects the state to cover your healthcare, your children’s university fees and your retirement.

All this to say that I don’t know whether the lifestyle I used to have in France would cost more or less if I transposed it to Canada. But that’s okay, because as I explained, some aspects of my lifestyle have changed. What I do know though, is how much I’ve spent monthly on categories like food, restaurants, health, haircuts, donations, trips or leisure in the last 24 months, to the penny and by currency. I know which percentage of my income comes from my salary and other sources. I know how much savings I have, and thanks to that, for how many months I can support my lifestyle if I lose my job. I know how much I can invest every month. I have allocated a budget for each category of expenses for the coming months, and from there, I know my savings forecast.

I could have looked for a ready-to-use tool, but some things never change. Let’s face it: it was just more fun to build one myself, and to tailor it to my exact needs. So I started one. I’ve dedicated hours to do and undo and redo. I don’t think I would have been willing to dedicate all these hours to a tool I wasn’t confident I would use for the rest of my life. Furthermore, it was never about building the tool as it is today, but rather about adding new features iteratively, as I became self-aware of the indicators I had come to need, and which I was very well able to function without before. The tool didn’t offer proper support for multiple currencies before it occurred to me it had become a problem. It didn’t offer monthly tracking of my investment objective before I finished building my safety net, and I started to invest a part of my additional incomes, simply because I didn’t need it. As I shaped it, it was both something I used on a daily basis, and a support for me to experiment with different personal finance management techniques (sometimes more one than the other). Actually it was not until very recently that I discovered personal finance is a thing, with lots of books and blogs extensively talking about it. And when I listened to my first podcast, I was amazed (and to be perfectly honest: reassured) to see that I haven’t missed much. But I was also glad to not have found them earlier, because a part of me thinks I would have gone too quickly over some important steps of my journey where it was important for me to stop for a while and take the time to think about the process. The child in me needed some time alone with his new toy before someone taught him how to play with it.

The tool, which I eventually named “Piggy” when I got tired of referring to it as “this app I made to keep track of my personal finances”, is no more than a translation of my current needs and views on personal finance management, and it’s never finished. For this reason, I would not necessarily recommend someone to adopt it as it is, no more than I plan to ever sell it one day. But I think now is a good time to take a few steps back and reflect on the beginning of this slow development I started. With luck, someone will find some inspiration in this.

How much do I spend?

As I mentioned, the first thing I wanted to know is how much I spent on certain categories of expense. And at the beginning, that was about it and I didn’t plan to embark on the whole personal finance management journey. I didn’t really see beyond simply measuring how much I spend on food or transportation, and which expense category is the biggest.

I could have just used the categorization tools offered on my online banking. Most banks support this feature, basically they assign a default category for each transaction on your statement depending on the merchant, and they let you change that category to better match the kind of expense you used your card for.

This is okay, but I find it very limited, at least with the banks I use. They don’t always let you define your own categories, some don’t let you change the category for things like withdraws at an ATM, and only some of them offer you to split a transaction into multiple categories. Typically, if I used my card to pay the bill at some restaurant where I took a friend for their birthday, I’ll want to split the amount across two categories of expense, like restaurant and gift for example. Besides, I own accounts in multiple banks, and for obvious reasons I wanted to have all my transactions aggregated in one place. Some banks let you connect their dashboards to your other banks’ data. I must say I haven’t given this a shot, but I wasn’t too fond of the idea of being more locked-in with my bank than I already was.

I figured there were some applications out there that I could just have used, and I’ve no doubt I could easily have found one that would have served me well. I already gave some reasons why I haven’t really considered them, but I want to talk about another one, which has to do with the concerns I had about privacy. I ended up creating a document on Google Sheets to start tracking all my expenses, and I do see how someone could easily make a case against trusting a free product from Google to store data that you wouldn’t want too many industry actors to exploit. But using this product offered significant advantages, such as the support for exporting your data into different standard formats, the possibility to access the document from any computer with an internet connection and sharing it with other people of trust (such as your life partner). Plus, Google has an API that you can use to read and write data from Google Sheets, which as a programmer I found to be a game changer if I ever wanted to automate something using the data I was about to collect there (which - spoiler alert - I eventually did). Finally, with all the skepticism you could reasonably have to a company whose business is to sell your personal data, Google still is a company I know, as opposed to some startup that I never heard about. I realize it’s a weak argument, but it did weight in the decision, and the point of this post is to be transparent. I wouldn’t be 100% honest if I didn’t mention it. And again, the last but not least reason being… you know, the well known “do-it-yourself-is-always-better” syndrome that I have, that I think we programmers all have to a certain degree for better or for worse. And most of the time for not so much actually (Github could randomly pick and delete one repository every day, I bet it would make no difference to the world 364 out of 365 days in the year).

So I started to meticulously keep track of every transaction, small or big, with every card, on every account from October 1st 2020. I started relatively small, with only a few columns like the date, the category, the amount, the bank account and a description, and soon enough I was able to draw some charts to visualize how my expenses evolved over the last two, four, eight months and so on, and I was content.

How much do I save?

This is the question that naturally came to me next. Although it’s a simple question, on a relatively short sliding time window (like the last 30 or 60 days), a lot of people actually don’t know whether they live beyond their means. It may seem surprising, but it’s only logical: if you don’t know how much you typically spend on your needs in a month, how are you supposed to know if you can afford this unexpected expense you want to make, like a weekend out with your friends, or the latest Playstation or iPhone? Maybe you’ll just take a quick look at your savings and try to roughly estimate it, but what if you repeat this process for several months in a row without realizing you’re constantly spending more money than you make? Eventually you’ll look at your savings and wonder how half of it disappeared without you noticing.

So I changed my spreadsheet and added a new tab where I started to keep track of my incomes. As for my expenses, it was fairly simple with only a few columns: the date, the source of income, the amount, and the provisioned account. It was quick and easy enough to do it retroactively in the last few months for which I traced my expenses, and from there to build a chart with the difference between my total incomes and expenses for each month. I heard somewhere that when it comes to building wealth, making money is not the most difficult part, it is to keep it which is actually the particularly tricky and difficult part. With this new chart, I was now able to read how much money I was able to keep at the end of each month, or how much I took from my savings.

Unsurprisingly, I found that when it comes to deciding whether I should spend money on something, basing my decisions on my visualizable capacity to not spend it in the last months rather than how much I have in the bank at the moment, really benefits my savings. But knowing how excessive I can get about certain things, I had to watch myself not to become obsessed by my new metrics at a point that it would have unreasonably affected my happiness. I find it perfectly acceptable to wait for another year or two before I replace my current laptop, but giving up on going out on a hike with my friends because I’m not ready to spend 50$ on a car rental might not be the smartest move. And if you insist on rationalizing it in money (which might not be the wisest thing to do by the way, but that’s a whole other discussion), you can argue that you may have to spend more on therapy when you end up feeling sad and lonely without friends. So in a way, it’s an investment on your future mental health. The same way that you might eventually spend more money on medical care and treatments than you saved by starving yourself. Although I was well aware of that risk, I could not help but to feel bad at the idea of ending the current month with a negative result, no matter how much I had in my savings account. I felt like I was losing at Google Sheets. There definitely was something in my limited little human brain that could not bear to see the cell turning red (that’s right, I used conditional formatting, I’m that good). It made no difference to me that in the previous eight months, I was able to keep an average of let’s say 600$ monthly. Ending the current one with a negative result of 50$ was just psychologically unacceptable. I knew my finances were okay, but I didn’t feel like my dashboard reflected that, so I had to tackle that issue with a technical solution, rather than by starving myself.

I had the option to leverage a specific feature I implemented to dissociate the date of an expense and the date of the actual transaction on my bank account. Having talked about this with other people, I know it can seem a little disconcerting but the purpose of it is actually rather simple to understand. Let’s say I take a plane in July to fly back to France. Knowing that in advance, I’ll presumably book my flight months in advance. If I buy my tickets in March and therefore associate this expense to the month of March, my dashboard will accurately reflect my account statement, but it will make it more difficult for me in the future to make sense of this big travel expense in March, while I spent practically nothing in July, even though I know for a fact that I had that trip to France. A typical answer I knew I would eventually want to look for on my dashboard when I originally started tracking my expenses would be how much money I spent on my last trip to France two years ago, so that I’m able to make an informed decision when provisioning a budget for this year’s. It may be easy enough to remember that I booked the plane a few months in advance, but imagine that I booked the hotel for that same trip in April, and at the same time, I also spent some money on a weekend in the back-country. Unless I choose to introduce a specific category dedicated to all the expenses related to my trip in France instead of having it all categorized as Travels, it will just be a pain to find out the answer I’m looking for. To put it another way: the general intent was to reflect the cost of my lifestyle on a monthly scale, more than having a faithful mirror of my bank statements. By the way, this is actually another element that reduced the number of potential options I had when looking at the apps I could have used instead of crafting my own solution.

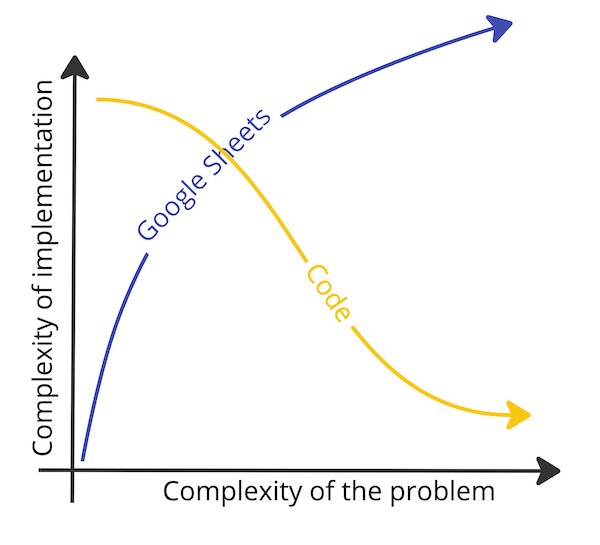

So why am I mentioning this? Because I have to save for several months before I can pay for my plane ticket to France. When I looked for ways for me to be okay with the red cells, the possibility to virtually smooth the big expenses over the previous or upcoming months crossed my mind. A bit as if I somehow granted myself a credit. I considered this solution for a while, but it conflicted with one of the goals that I just mentioned. Plus it kind of had this hacky flavor, which I didn’t enjoy so much. Shortly after, I thought of another better solution. And it is in fact quite a simple one: I introduced a new chart that represents the evolution of my savings over time, month by month, calculating the savings at the end of a month by simply adding that month’s result to the state of my savings at the end of the previous one. This way, the curve can sometimes go up and sometimes go down. I’m now okay with it as long as I keep an eye on the global trend, and make sure I cut some expenses when I expect my savings to run too low. Managing money in the couple I felt both amused and stupid to find myself, after several years of working as a programmer, discovering the joy of spreadsheets and how quick and easy it was to create insightful representations of my data without producing a single line of code. I’m exaggerating a bit, but I did find it fun and useful to learn about some powerful functions I had no idea they existed. But again: things never change. Eventually recess was over and I opened my editor and started writing some code. But as mentioned earlier, thanks to its API, I didn’t have to rewrite everything I had built in Google Sheets, instead I could build whatever I needed on top of what already existed. I’m sure I could have found a way to implement those new features with only Google Sheets, but I had a feeling it was just going to be unnecessarily complicated. For the sake of conscience, I searched and I found this very serious study that managed to produce this very insightful chart here, and after that my mind was made.

This feature I’m talking about has to do with the way my partner and I manage our money as a couple. First, I want to say that I’m well aware this is not going to work for everyone. However, I found it useful to bring up this matter, and to deliver the current state of my thoughts so that they can be openly discussed, as I believe we would all benefit from more transparency on this. We are all specialists when it comes to convincing ourselves that no discussion is necessary about this topic and that things work fine naturally, until a conflict eventually breaks out and we are forced to address the issue, maybe under the worst circonstances. Luckily, I have no memory of such an event that would have occurred to my partner and I. What we do is prevention, that I’m sure one day we will be grateful to have done. At least, it’s what I believe, and if I do this little disclaimer, it’s because of some opinions I’m going to present, of which you may not always be a huge fan. They are the temporary result of a process of thinking that is never finished, and I try to keep a mind as open as possible and to look at other people’s choices with as little judgment as possible.

As for all complex topics, my mind is never definitely made as to what is the ideal solution for a community - may that be a family household or a whole country - to share their resources. In the history of men, we’ve seen different approaches being experimented, which are all interesting to study. And I must say that when talking about vaste communities such as whole countries like France or Canada, I’m not too bothered by the wealth gaps that exist between people of those communities. I’m not, because to me it shows that opportunities exist for anyone to create a legacy, to gain a certain form of freedom or independence, as opposed to arbitrariness. Your owner can’t evict you from your house if you’re the owner of the house. The same way that getting to diversify your sources of income will make you less dependent on your employer. This is maybe the best source of motivation: to gain a certain level of control on your fate and I don’t think it’s healthy for a society when people start blaming others for their success. Actually I think the opposite, and I look at this as a symptom of a society in decline. I’m not saying everything is perfectly balanced, injustice exists of course, as it has always existed since the dawn of men. I’m just saying, if complaint is all we grant ourselves, then we choose to do without other less violent and potentially more efficient means to improve our condition. Quoting Orelsan: nobody loves rich people, until they become rich themselves, you’ll have to pardon his French.

So I don’t have a philosophical problem with capitalism. As for the market, I consider it to be the best (or less terrible) tool available to solve the difficult equation of the access to resources at a scale as large as one of a country, at least as long as we maintain a few safety measures to help contain its most undesirable side effects. I’ve lived in two countries, both rich, and I’ve essentially traveled in rich countries, and yet I saw people sleep in the street. In Montreal, when temperatures start dropping in October at the approach of winter, I think about those people and it fills my heart with sorrow. I was in San Francisco for Google Next 2018, and stayed over the weekend after the conference to visit, and I was shocked to see maybe a hundred homeless people with their tents installed before city hall. I could go on but my point is that I’m well aware of what happens to the poorest in a society that trusts the market with everything. I prefer to live in a country where one’s dignity is not traded with money, and fortunately a majority of people agree with this principle. This explains why, when governments reach the extent of their ability to act, we see initiatives like soup kitchens or other charity events emerging. States have duties of their own though, to arbitrate and regulate. Consider the example of global warming and the carbon emissions of the 10% richest French people that are four to ten times the emissions of the 10% poorest. Where some say states should take the money from the rich and allocate it to the energy transition, I would rather see them impose quotas on things like the number of kilometers you get to do by plane per year, rich and poor alike, just like you only get to drive as fast as 130 km/h on French highways, no matter how much you spent on your car. Just let the rich keep their money, states don’t need it. Donald Trump can throw away his legacy in his cascade of Evian in Manhattan, I don’t give a hoot as long as I know there is enough for everyone else to drink. Money is a straw-man, the real injustice is the power of nuisance exercised by the richest on the poorest, so let’s talk about that instead. Someone would first have to establish the unwavering causal link between a person’s excess of money and others misfortune, before saying otherwise. In the meantime, we’ll have to continue treating poverty as the complex matter that it is, with its multiple causes that one does not solve just by throwing some money on them.

Anyway, back on the topic of managing money as a couple: all this to say that, on the contrary, when it comes to my home, I turned out to be a convicted socialist. This is because a couple is different from a country in the way that it’s surprisingly easier to build a consensus on the conditions for a perfectly egalitarian system when you are two instead of millions (although there are definitely some challenges there as well). Unexpected, isn’t it? Besides, you get to choose your life partner, whereas your opinion matters significantly less when picking the individuals living in your neighborhood, your town or your country. I’m going to say something that may offend the most humanistic of my readers, yet it’s not something that strikes me as very subversive. If I choose to build a life with someone, chances are I’ll be inclined to adopt a somewhat egalitarian way of life. I can’t imagine for a second that an extremely wealthy person would find the idea of letting their other half live in poverty bearable. But consider the case of my imaginary neighbor who chose to live on his modest retirement around the age of 50 while in perfectly good shape and health, to fully dedicate himself to his passion. Let’s go further and add that his passion is to hunt, and his dogs that he keeps locked outside behind fences between two hunts continuously wake me up in the middle of every night. Without going so far as to wish him a life entirely eaten away by the specter of financial precariousness, I would find it revolting if part of my income were taken from me in order to finance the vacation on the beach of this not so brave gentleman, when I have to finance mine by sacrificing some of my own passions. Be careful not to over interpret that and accuse me of being ideologically opposed to a system like employment insurance. I toy with this deliberately provocative and somewhat exaggerated example to make the point that the consequences of a system that would push egalitarian logic to its extremes can be unfair. In reality, all citizens are in favor of a system that is not egalitarian, but equitable. The problem is that no one agrees on what that means.

Even in not totally egalitarian households, we will necessarily see a form of balancing appear naturally, inevitable from the moment there are some shared resources, presumably to the benefit of the person with the smallest income. For example, many couples I know use a joint account to which each member of the household contributes according to a more or less clearly established policy. Typically, this joint account will pay for groceries, rent, and other common household expenses. Apart from contributions to this account, each member can dispose of the money they have left as they like. With this system, the person who makes the most money will have more to spend on their personal expenses, so in this sense it is not strictly egalitarian even if both members contribute the same to the joint account (note that a lot of people may find that perfectly equitable). But even then, if one of the members decides to use their money to equip the household with a new fancy sofa, it is hard to imagine how they would prevent the other members from sitting on it on the pretext that they didn’t pay for it.

Since the beginning and to this day, we never had a joint account, and the possibility to open one only came out on the occasion but we never seriously considered it. We have individual accounts of our own, for the simple reason that we’ve always functioned like that. We never felt like we would benefit from opening one, because from the start we simply organized ourselves in a way that both of us would contribute to our common expenses evenly. Concretely, we would ask for two payments at the cashier, and when it was not possible, we would transfer some money from one account to the other to rebalance. Until two years ago, when I started to measure our expenses, this was not clearly defined. It was more of an unwritten rule to which we both roughly complied. But starting to measure what actually comes out of which account naturally led to a conversation that defined this more formally. And as it turned out, we both agreed on a perfectly egalitarian repartition system. The amount of pocket money that each one of us would have at the end of the month would be strictly the same for both of us, and completely decorrelated from the money we individually make. The formula to determine that amount could be expressed as follows.

X = ( [ (I + J) - K ] / 2 ) - L

Where,

X= the surplus budget for the member’s personal expenses at the end of the monthI= the total income of the member for the monthJ= the total income of the other member for the monthK= all the common expenses for the monthL= the portion of the budget for the member’s personal expenses that has already been spent during the month

In plain english, that would be: for the current month, sum all our income, subtract our common expenses, divide the result by two, and finally subtract the personal expenses already made if there are any. So hypothetically if we both make 2000$ in the month and our common expenses are 3000$, but I already spent 50$ on a video game, that leaves us with 950$, including exactly 500$ for my partner and 450$ for me. Note that the result is the same if one of us makes 2500$ and the other makes 1500$. Again this works for us and we’re both perfectly okay with this system, but I realize there are a lot of different situations out there and what works for us might not work for everyone. For all I know, this might not suit us anymore at some point in the future and we might need to adjust it. But if you wonder what motivated this choice, it boils down to one key principle: money is power, and for a couple to function healthily, power must be balanced as evenly as possible. This is why we think this is the fairest system, even though (or should I say: especially because) we both have different incomes. Our biggest expenses are the one we associate with our common needs. Typically, those expenses consist of things like rent, food, electricity, internet, insurance or transportation, but exclude others like restaurants or travels. When we have a decision to make that will impact one or several of these expenses, like moving out to a different apartment, or changing our food habits, etc. one thing we want to make sure is that we both are able to cover half the total of these expenses. This is a rule of thumb that is meant to ensure power is distributed with a minimum of equity. Because we are both able to pay for at least half our needs, no one can legitimately claim their voice counts for more than the other’s. Also no one gets the impression that they are living beyond their means. But if you’ve followed me carefully, you noted that the formula goes further, by making the one with the highest income redistribute a portion of their money to the other member of the couple. Coming back to my hypothetical example from before: if member A makes 2500$ and member B makes 1500$, after the 3000$ of common expenses are paid, they are respectively left with 1000$ and 0$, so member A has to give 500$ to member B, so that the remaining 1000$ are equally distributed. Obviously, from a purely economical point of view, this benefits more to member B who makes the least, which has an undesirable side effect, that is to give more power to member A who makes the most. True as it is, it should be reminded that at this point the essential needs are already covered, therefore this money is only supposed to cover non-essential expenses, which considerably reduces its intrinsic power. In personal finance jargon, those are referred to as wants as opposed to needs. But mostly, this prevents certain situations from happening, that would potentially be even more harmful for this balance, here is how.

Let’s say I get a 500$ raise, so I want to move to a bigger apartment. Without this redistribution system, the conversation will not be even. Because if the new rent is 200$ higher, this means that to benefit from this surplus of comfort, it will cost my partner an additional 100$, which she will have to give up saving or using for something else, whereas I won’t have any sacrifice to make, actually I’ll even be 400$ richer. No need to explain how this could create a conflict. But with our redistribution system, if I get the same raise, this means we both become 250$ richer, therefore the balance of power is not altered, and we can have a less conflict prone discussion about whether moving to that new apartment is worth 100$ for each of us. Note that this works the other way too, if for example I decide to take another job which is less paid, the process is strictly the same. By giving a share of the power back to the person who didn’t get a raise, we allow the decision-making process to be more democratic, which I don’t think I need to explain either how this benefits the health of the relationship.

It is essential that both members adhere and understand the crucial role that this money transfer plays in the balancing of powers in the couple. By prioritizing the preservation of this balance over everything else, the one who makes the most money renounces, in the name of this higher principle, to consider the money they give as their own. Thus, they also renounce claiming ownership of what was bought with this money, or the future benefits if it was invested. This goes against certain capitalist reflexes. Reciprocally, the person who makes the least money, renounces looking at this as charity, but rather as an assurance that their decision-making power is valued and preserved, whereas without it, it is the principles of equality on which the relationship is built that are eroding, putting in danger the very existence of the couple. In other words, as long as we continue to prioritize the equal sharing of powers in our relationship, we’ll both look at these rebalancing operations as a necessity, and it is not possible to revoke them without replacing them with another measure presenting guarantees at least as strong. This all makes sense when the couple is making major changes that alter the financial balance, such as when one reduces their working hours to go back to school, build a house or take care of a child.

We start to see the limits of such a system if the income gap widens between the two members of the couple. Adopting this way of doing requires a less strong engagement to the underlying principles in the case where the amount of redistributed money is marginal. But it can happen that the gap widens in a very important and involuntary way. This is the case, for example, if one of the members suddenly sees their income drop, because they have lost their job and have been forced to accept another less well paid position. In such a situation, it may happen that this person is no longer able to cover their share of essential expenses, which technically makes them financially dependent on the other. If this were to last, under the principle of equitable distribution of powers, the couple would have to make the decision to reduce the cost of their lifestyle, even if the wealthiest person was able to cover for their partner’s loss of buying power. But it is easy to understand how this may not be desirable. Imagine the case of a person on a minimum wage, engaged in a relationship with someone who makes $500,000 a year. We can assume that the person who makes more money will be tempted to push the standard of living upwards, which would be difficult for the other to oppose, even though it could eventually provoke some form of psychological complex. The whole thing about each member of the couple paying for half the essential expenses is ultimately no more than a way to find some sort of red line beyond which the engagement to the underlying principles I talk about can begin to falter. But really, it’s not just about where you place this limit. The idea is that at some point, adherence to the principles alone may no longer be sufficient to keep doing things this way. And eventually it will become a necessity to take into account elements other than the sole financial aspect, in order to guarantee the balance of power in the relationship is healthy. The nature of these means, which can be very diverse, will vary from one couple to another. In any case, if spending less money so that it is more in line with the lowest income is not considered, then other ways will have to be found to make the situation acceptable to the person who is financially dependent. Because it is for this person that the situation is the most difficult to bear. Nobody wants to be dependent.

As far as we’re concerned, the gap isn’t big enough for the one of us with the highest income to feel frustrated, and all this long development that has become clearer over time really started from a very basic and uncomfortable perspective, that is to see the one of us who makes the most money renew their iPhone every year, while the other would have to count their pennies just to afford a pair of socks (I might be exaggerating a bit to make my point).

So once we clarified and agreed on how this was going to work, we needed a small tool to help us implement it. While not a particularly difficult problem to solve in theory, looking at the spreadsheet when the month is closed, the information of who owes how much to whom was not immediately readable, and could be a little confusing to get, as in practice, when we had 3000$ of common expenses, 1500$ did not necessarily came out from our respective accounts. Maybe member A covered for all the common expenses, so in this case, member B owes them 1500$. But wait, potentially not that much if member A has made more money, unless member B has spent money for themselves, so we’ll have to subtract that, anyway you get the general idea. So I added some necessary information that the spreadsheet was missing, such as the owner of each account, and whom a given expense is associated with (leaving the column empty if it is a common expense), then I put on my programmer helmet and managed to produce a small script to just give us the information we needed.

> ./hit-me -month 2021-08

XXX owes YYY 167$

What else?

I have yet to talk about investment and the few implications it had on the way we manage our money. I also would like to share on how I budget my expenses, some challenges that come with having to manage different currencies, as well as some examples of things I tried more recently in order to optimize my expenses. But this article is already too long, so I think I’ll keep all that for a second post that I’ll publish later.

In the meantime, if you managed to read this first part, and you have some feedback you want to give, or want to talk about your own experience, feel free to do so in the comments section. I would be interested to read you.